Coburn's Laws of Ergonomics: How UofT alumn Dr. Don Coburn altered the design of dental practice

Dr. Don Coburn 5T1 had likely not yet practiced on one of the first fully reclining lounge chairs when Ronald Cox sat down as a patient in the 1960s. Cox was a mechanical engineer by trade, and as he and Coburn navigated the dance that is patient and dentist, they also got to talking about how to make that dance more efficient. It was a conversation that soon led to a revolution in ergonomic dentistry design.

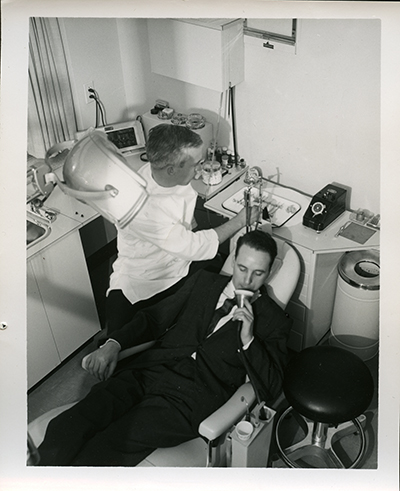

Before the revolution of lounge chairs in the late 1960s, most dentists worked on the standard Ritter J chair. The chair did not recline so dentists stood as they worked on their patients. Just a scant few years prior, one of Don’s friends from the Pankey Institute of Dentistry had invented the lounge chair. Yet there really had been no thought to how the rest of the practice needed to shift to accommodate the change.

With the old chair, for instance, a cuspidor with running water allowed a patient to spit. But once the lounge chairs came into vogue, the old spittoon system no longer worked. To spit, the patient would need to sit up, halting the work being carried out.

Where many saw patients and instruments, Coburn saw systems

That wasn’t the only issue. “Dentists were still standing,” says Andrew Coburn 8T0, Coburn’s son and business partner relates. Chairs were at the height of barber’s chairs, meaning dentists were on their feet all day, developing varicose veins and back problems.

That all changed when Coburn partnered with Cox to create Cox Systems. Under Cox systems, Coburn completely redesigned the dental unit, and in July, 1969, was issued his first patent for the design. With Cox’s added mechanical savoir-faire, the pair also invented a high-speed suction device to replace the now-awkward cuspidor. The inventors soon attracted Wilson Southam (of Southam Newspapers), who came aboard as an investor, and the company soon became known not just as a company for ergonomic dentistry design, but democratic, progressive work place practices.

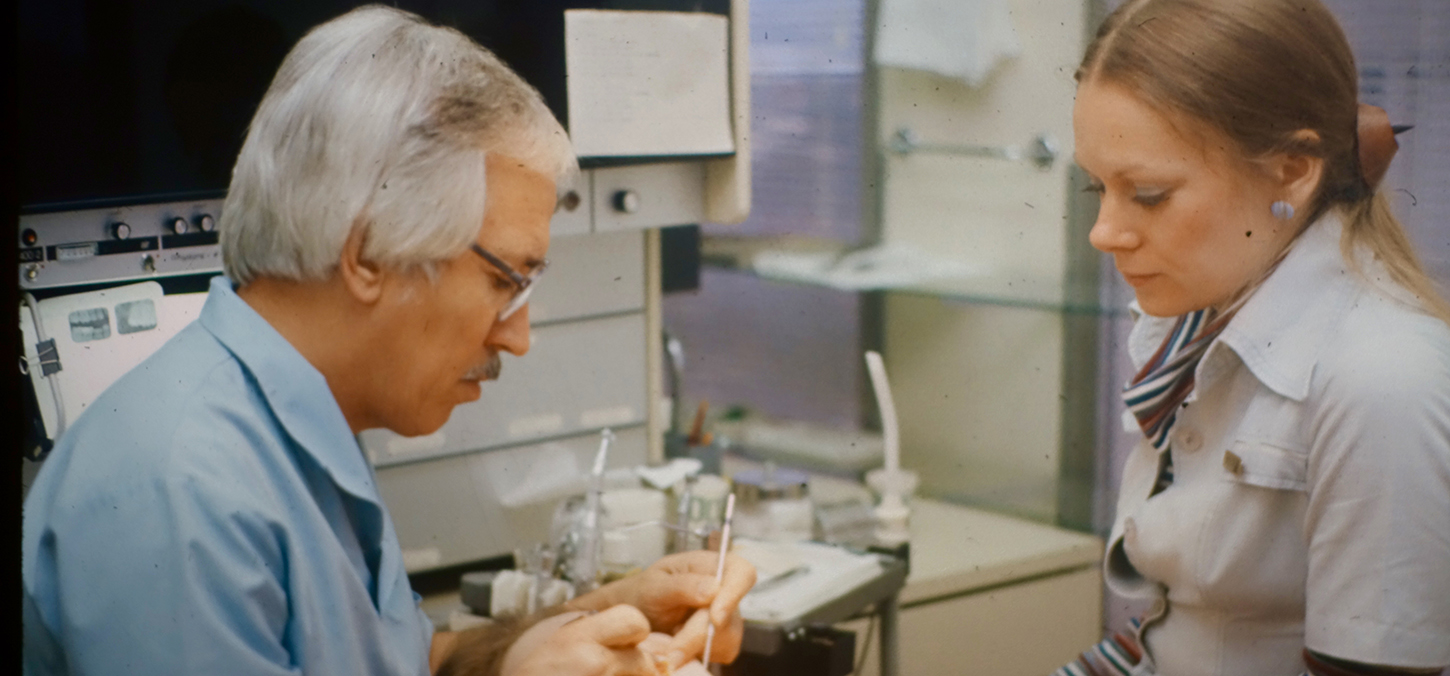

As Coburn saw it, the invention of the lounge chair was just a starting point to re-imagine the spaces that the practice of dentistry inhabits, as well as its workflow. Where many saw patients and instruments, Coburn saw systems—and those systems could be improved upon. Under the Cox Systems umbrella, Coburn altered the arrangement of storage, chair, instruments and instrument placement, and lights. The design was modular, where some parts of the unit could be moved. Everything was designed to speed up practice and increase a patient’s comfort.

CDA president elect and a 2017 Award of Distinction winner, Dr. Larry Levin 6T9 recalls the project vividly. Between third and fourth year Levin was hired by Coburn to help him with a research project funded by the government, to study the ergonomics of dentistry. The project called for the installation of a time lapse camera in ten different dental offices across North America. It was Levin’s job to install and run the camera for which Coburn had designed a special scaffolding system. Two side supports rose on either side of the dental chair, joined across the top with a crosspiece, upon which the camera was mounted.

The research experiment had likewise been meticulously designed. Each dentist was to be filmed completing the same action: in this case, a two-surface amalgam on an upper molar. The camera rolled for about half an hour for each of the procedures, snapping film at approximately ten frames per second. Through each frame the camera peered down on the heads of the dentist, assistant and patient, recording hand and body motions that were later be analyzed.

Coburn’s was one of the original ten offices studied. It was obvious even from the research film that Coburn had already carefully considered the flow of dentistry. “Don had spent a lot of time thinking of where to put things,” says Levin. “He completed the same task as the other dentists, but the time lapse film looked like Don was doing it in slow motion. Don was doing each move smoothly, arms and back positioned comfortably. The others were zipping around, sometimes even leaving the room to get the amalgam. Assistants were reaching into the cupboards to grab things—it wasn’t organized.”

Coburn’s comprehensive research was rolled into a new line of dental office design. Hallmarks of the design suite included the storage of most of the equipment behind the patient’s head. “Nothing was in the patient’s field of vision so they were more relaxed and didn’t see anything scary or frightening,” says Levin. A tray could by moved conveniently between the dentist and his assistant. A drill could be clipped on to the tray for easy use. The cabinetry was shortened to complement sitting dentists. Don also designed a sink for the cabinet to provide easy access to hand washing.

“Today those features have been adopted by many manufacturers,” says Levin, “but at the time it was revolutionary.”

It was also effective, says Dr. Andrew Coburn 8T0, son and business partner of Don Coburn. “Dentists went from spending thirty percent of their time working to eighty percent of their time working.” The office units were sold in the U.S., Canada and Europe.

Levin, who was invited to work at Cox Systems one day a week after his graduation, and to associate with Coburn in his Hamilton office, also recalls the kind of impact it had on his practice.

At the time it was revolutionary

“I also worked for a while in an office in Brampton at the same time I was starting with Coburn. The equipment there was traditional. It was terrible to work with, as opposed to the ergonomically designed equipment Coburn was working on.”

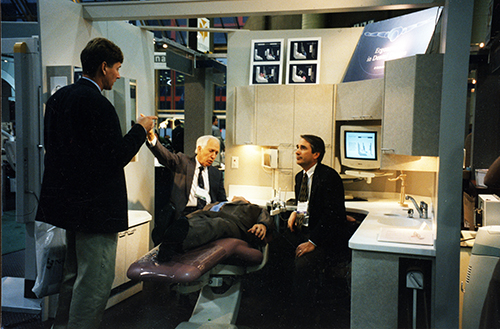

Years later, after a fire destroyed Andrew Coburn’s practice, the father and son collaborated on yet another design for a dental unit, one that integrated a computer. The team went through the laborious and time-consuming exercise of examining every aspect of practice, the results of which were incorporated into the new unit. From keeping the areas clean to improving speed of transfer from one piece of equipment to the other, to organizing boxes, the unit was a contemporary marvel of technology and ease. The sink was made to turn on water via a foot pedal, for instance, with paper towels handing down over top. Even glove and mask distribution was deliberately designed: a plexi-glass pane covered the glove boxes, keeping them sanitary. The father and son team formed a company, Coburn Dental Systems, to market their designs, which were once again sold across the U.S., Canada and Europe.

“We made the dentist’s cockpit,” says Andrew Coburn.

Don Coburn was recognized for his contributions to dentistry and to the Faculty of Dentistry (he was a clinical associate in dentistry at the Faculty for years) with the Faculty’s Award of Distinction in 2002.

Images: Courtesy Dr. Larry Levin and Dr. Andrew Coburn

Top centre: Don Coburn works on patient; right: Larry Levin installing cameras during research project, circa 1968; left: participating dentist works on patient; bottom left: patient uses spitoon during filmed procedure; bottom right: Don and Andy Coburn showcase their dental suite design at a trade show