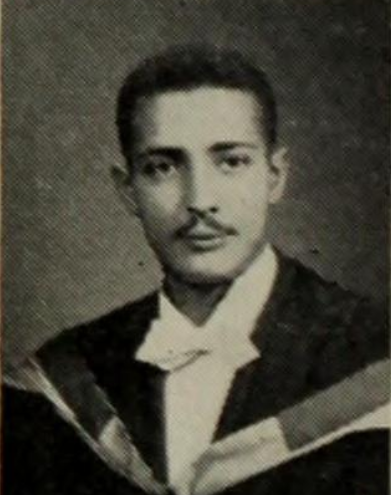

Fighting the active horse of prejudice: diversity champion and inclusion activist Arlington Franklin Dungy

Arlington Franklin Dungy, inclusion activist, was one of Ontario’s first Black dental school graduates. First making a name for himself as a healer, Dungy later built a career around cutting a path wide enough for many more students from diverse communities to follow in his footsteps.

Originally from Windsor, Ontario, Dungy earned his DDS from the University of Toronto’s Faculty of Dentistry in 1956. Just over ten years later, in 1969, he was named chief of paediatric dentistry at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children. (He earned his specialty diploma in paediatric dentistry from U of T Dentistry in 1970).

After a decade of shaping the lives of tiny, medically-compromised patients in Toronto, in 1981, Dungy was recruited as chief dentist for Ottawa’s Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario.

“I can remember, in my youth, that prejudice was an active horse in the community… and that is an experience that shapes your being forever”

He became an adjunct professor of surgery at the University of Ottawa’s Faculty of Medicine, where Dungy also helped found a student affairs office. He was later named associate dean, alumni and student affairs. There, he used his experience to motivate changes to education policies that would ripple down through generations.

“I can remember, in my youth, that prejudice was an active horse in the community… and that is an experience that shapes your being forever,” Dungy was quoted in a 2006 Indigenous Works newsletter.

He drew on this experience as he founded an initiative to encourage Indigenous applicants to the medical school. He became the first director of the Indigenous Admissions program for the U of O’s Faculty of Medicine in 2006.

The program calls for eight spots to be held for qualified Indigenous applicants each year, helping to boost the numbers of Indigenous physicians in Canada. And there is a pressing need for greater representation.

“Currently, there are no more than 200 self-declared Aboriginal doctors in Canada,” Dungy said at the time. “There should be about 1,500 – 2,000 to be representative of the population.”

Over a decade later, those numbers are still staggeringly low. According to the 2016 Census, less than one per cent of physicians and specialists in Canada identify as Aboriginal. Meanwhile, Indigenous people make up more than 4.5 per cent of the population.

Dungy, though, looked forward to a time when other schools would likewise challenge themselves to become more inclusive of Indigenous applicants.

“If all took the same approach, we could make a huge dent in the disparity of [Indigenous] representation,” he said.

“Arlie,” as he was known to friends and colleagues, passed away in 2016.

With files from IndigenousWorks

Yearbook photo (no credit), DDS Class of 1956