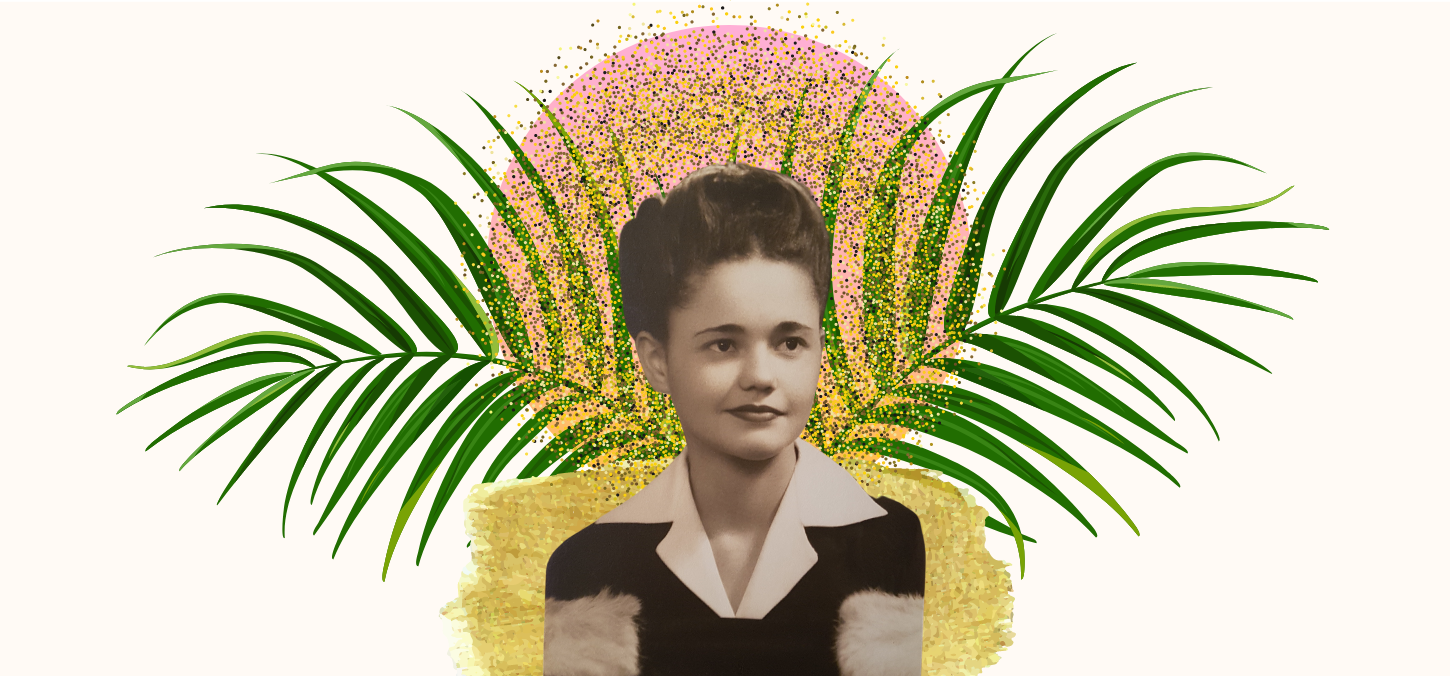

Margaret Hatton: a pioneer in dental research and teaching

By Diane Peters

Margaret Hatton 5T2 PhD (née Brown) was one of the quiet forerunners of dentistry research in Canada. She completed her PhD in Dentistry in 1952 and spent a decade doing orthodontic research at a Faculty-affiliated institute.

She was also a popular lecturer, teaching for decades at the department of zoology at the University of Toronto — exploring genetics long before it was a pivotal part of biological research and understanding.

Hatton was a pioneer for her achievement in academia and for establishing a career as a mixed-race woman — and mother — at a time when gender, family demands and racial background prevented many from having a career in science at all.

She faced many barriers. When her early work was covered by the local media, they were belittling stories that called her a “lovely girl” and a “snake charmer” although she was just showing and explaining reptiles.

While she worked for decades at U of T, she never received tenure or a full-time appointment.

Margaret Brown was born on November 7, 1923, in Montego Bay, Jamaica. She was one of eight children and her mother was of mixed race while her father was white.

Daughter Deb Hatton says she saw her mother’s childhood diaries and in one entry, Margaret lamented the poor treatment of Black servants by the students at her private school. “For a child raised in an environment like that, she had pretty sophisticated and intelligent observations.”

Margaret loved science. While she could easily have remained in Jamaica and married, leading a comfortable life, she chose to leave. World War II meant that Europe was unsafe, so she looked to Canada and the University of Toronto’s University College.

“She came here completely alone,” says Deb.

In 1946, she completed her BA. She was then accepted to the PhD program in Dentistry. In 1952, she completed her thesis, “A Comparison of the Patterns of Clinical Eruption of the Deciduous Teeth in Man with Growth in Width of the Dental Arches.”

By then, she was married to John Hatton, a U of T grad who worked as a scientific research librarian. After completing her PhD, Margaret was hired as a senior research fellow at the Burlington Orthodontic Research Centre.

This centre, which was run by Dentistry, saw Margaret conduct research on craniofacial differences in children treated by orthodontics compared to control groups and the dental public health impact of malocclusions in children.

Both Margaret’s thesis and her subsequent work integrated the importance of genetics, which was new thinking at the time.

Deb says these were productive years for her mother, but she did face sexism at work. Her male bosses, would often be upset that she didn’t include their names on her published studies.

Her work got noticed. In 1960, the Canadian Dental Association gave her an award. In 1968, the University of Michigan requested a copy of her thesis for their library.

In 1962, Margaret took on the role of special lecturer in the department of zoology at U of T. She often integrated information about craniofacial features into her teaching.

Her classes, especially her first-year course on genetics, were hugely popular thanks to their intriguing content but also Margaret’s charisma. “She was such a character,” says biology professor emerita Ellie Larsen, who co-taught with Margaret. She recalls her colleague captivating the lecture hall when she spoke.

“Years later, when meeting students who took the course, they do not remember me. But they remember Dr. Hatton!” she says.

Margaret worked part-time at U of T and focus on teaching while raising her three children. Larsen recalls her friend and colleague being determined to restart her research later in life. Around that time, however, John became sick and she was unable to devote herself. Margaret retired from U of T in 1989.

Margaret died on October 25, 2020, leaving behind her three children Deb, Roz and John, a son- and daughter-in-law and one grandchild. And she also left and an indelible mark for women in science and academia.

Banner by Rachel Castellano