Faculty researchers earn $2 million in CIHR grants

By Diane Peters

Pain and implant failures are the target of funded studies

Canadian Institutes of Health Information (CIHR) grants are highly competitive, but two U of T Dentistry researchers have been successful in the latest round, earning them a collective $2 million in funding to support innovative research projects over the next five years.

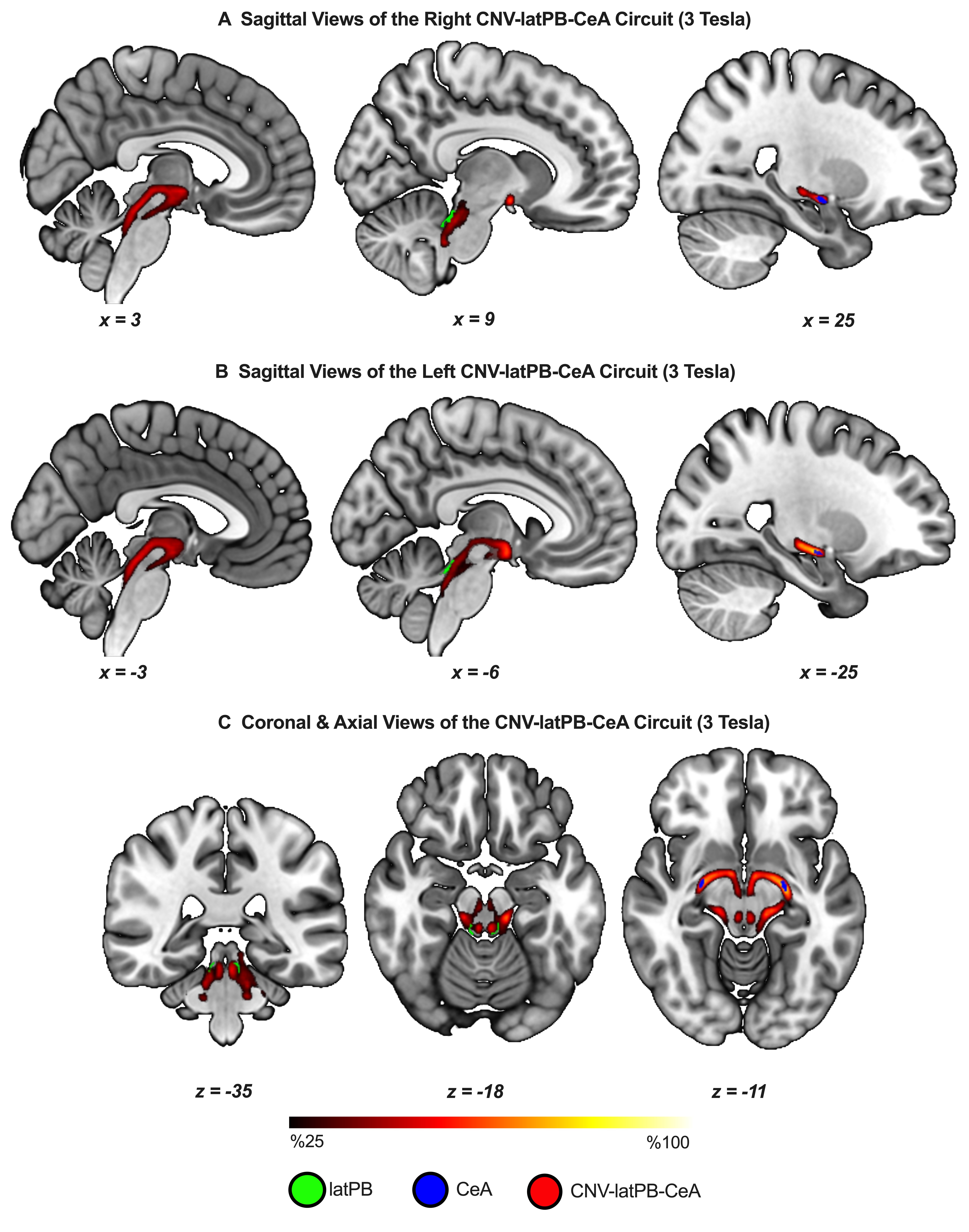

Associate professor Massieh Moayedi seeks to understand pain on a neural and emotional level through the project titled Determining the Neural and Pharmacological Mechanisms of a Novel Affective Orofacial Nociceptive Circuit, which earned a $1 million grant.

Moayedi, who is working with U of T Dentistry associate professor Iacopo Cioffi and professor David Finn at the University of Galway, will be exploring a novel neural circuit — recently discovered in his lab — and its role in orofacial pain. As well, the team will try to understand how this circuit is impacted by endogenous cannabinoids, also called endocannabinoids, which are cannabis-like molecules produced by the body.

“The goal of this grant is to see whether this pathway is involved in acute or chronic orofacial pain and then see if its activity is modulated by endocannabinoids, because endocannabinoids affect emotion and pain.”

The study will include healthy volunteer subjects with a painful orthodontic separator in their mouths, plus people already in pain with temporomandibular disorder.

“We’re not doing things in a lab with someone with a white coat with very strict settings and controlled environments. We’re sending you home and you live your life and then come back in the lab and we measure things,” says Moayedi. This allows the team to look at pain from a so-called ecological model, taking into account factors such as context and emotions, as well as physiology.

“The ecological model of pain is important, because the context of pain matters, and your control over that pain matters.”

Understanding these connections could lead, in time, to better treatments. That could take the form of existing drugs, new medications, or formulas derived from cannabis, as its cannabinoids might effectively target this system.

Getting this right, over time, could make a significant difference to helping people in pain and reducing opioid addiction rates, says Moayedi.

Another $1 million grant targets the common problem of dental implant failure, particularly for higher risk patients, such as the 2.3 million people in Canada with osteoporosis. “Lack of stability in dental, craniofacial and orthopaedic implants in osteoporotic bone remains a primary cause of clinical failure,” says associate professor Karina Carneiro.

She and her collaborators have a plan to tackle this concern on two fronts by using a new biomaterial for the implant itself and then adding in a topical application to aid in bone remineralization.

“The overall goal of the project is to combine DNA gels and 3D printed titanium implants to establish a hybrid implant system,” says Carneiro of the proposal called Towards a Novel Implant System: Combining DNA Gels and 3D-Printed scaffolds for Osseointegration in Osteoporotic Bone.

Her co-principal investigator is McMaster University associate professor Kathryn Grandfield, an engineer who has developed new approaches to titanium implants.

Carneiro, who researches biomaterials, tissue biology and wound healing, has been developing DNA-based materials for supporting mineral growth since she joined U of T Dentistry in 2016. In recent years, she’s published papers showing that one- and two-dimensional DNA nanostructures can produce hydroxyapatite, the main mineral in mineralized tissues such as tooth and bone.

She made the leap to 3D materials in collaboration with professor Christopher McCulloch 7T6, 8T2 PhD. “We showed that osteogenic cell lines remain viable when seeded on DNA gels.”

This five-year grant will allow the team to fine-tune this dual approach that will eventually lead to dental implant systems that will stay more stable, even in patients with osteoporosis. And since implants in other parts of the body can also fail, this system could work for other craniofacial implants, plus orthopedic implants used in other parts of the body.

These well-deserved grants show, once again, how dentistry research can use the mouth as proof of concept in better understanding critical components of overall human health.

Top photo: Carneiro in her lab (Jeff Comber)