Faculty fibrosis research earns provincial grant

By Diane Peters

A team led by Faculty of Dentistry researchers has earned a total of $12 million in funding to better understand the mechanisms behind the development of fibrosis in the body.

“Fibrosis is involved in about 45 per cent of deaths in the western world. If you have heart disease or idiopathic lung disease, it’s all about fibrosis,” says principal investigator, professor Chris McCulloch 7T6.

Fibrosis, which is excessive connective tissue that develops mainly in organs, is also a defining feature of periodontal disease. This project will look at fibrosis in the mouth, heart, kidneys and skin.

“Fibrosis is an underappreciated silent and slow killer,” says Boris Hinz, a member of the research team, who is a distinguished professor of tissue repair and regeneration, cross-appointed to the Institute of Biomedical Engineering (BME) and the Faculty of Medicine. “Fibrosis develops when body repair processes intended to heal damaged tissues go awry and degenerate tissues instead. This process can go undetected for months and years and is often only diagnosed when organ function is significantly reduced.”

Also working on the project is associate professor Laurent Bozec, a specialist in atomic force microscopy.

U of T professor Andras Kapus, a cell biologist at St. Michael’s Hospital and Igor Jurisica, a bioinformatics specialist with the University Health Network, round out the team.

The money comes in the form of a $4 million operations grant from the Ontario Research Fund (ORF) and the rest was matched through industry and institutional partners.

This operations grant follows the $6.5 million earned by the team in 2017 from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and the ORF to purchase equipment, including an atomic force microscope.

That round of funding also led to the creation of the Fibrosis Network, a Toronto-based group serving as a research hub to study this health condition.

The project will also seek to understand how inflammation, which precedes the development of fibrosis, works in the body overall. Often, inflammation is systematic: when people have cardiovascular disease, they also have periodontal disease. Understanding fibrosis could help illuminate how and when body-wide inflammation happens.

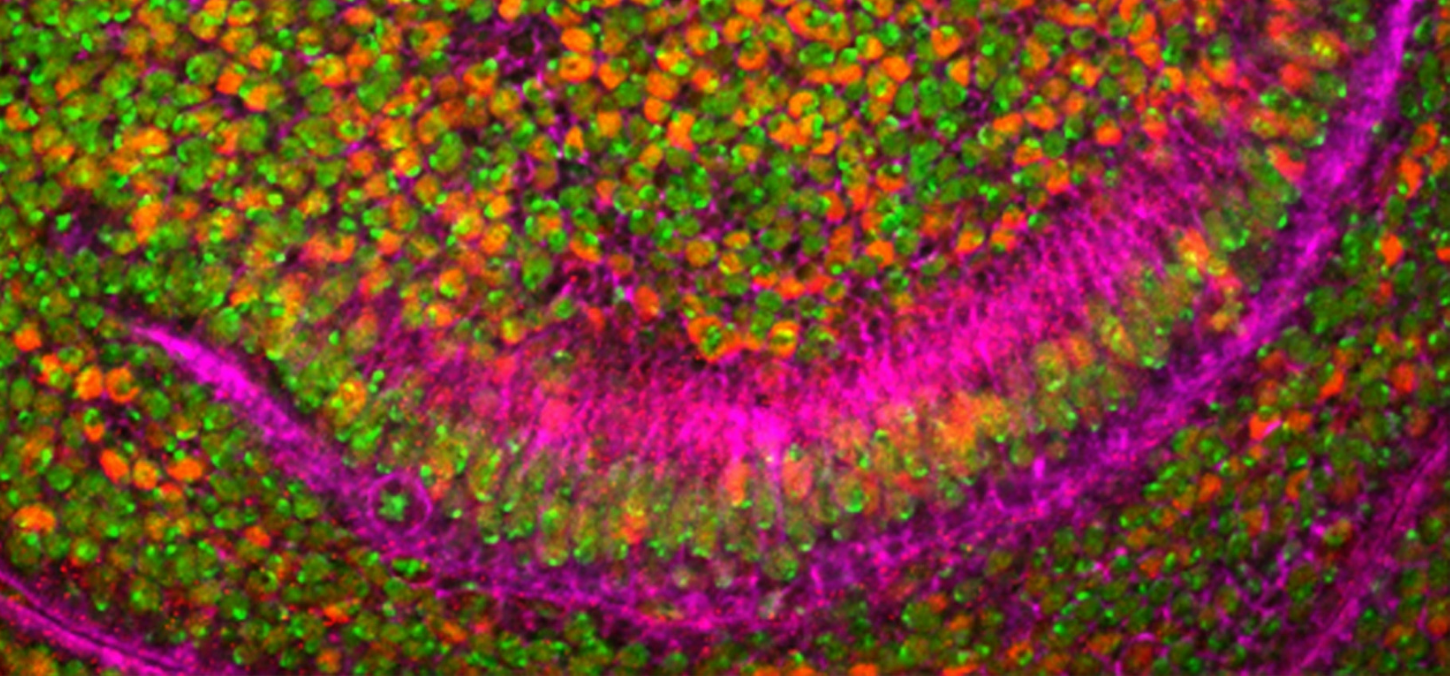

Hinz says his own work focuses on the cells that produce fibrous tissue called myofibroblasts. “I believe, if we can understand how these cells are activated in fibrosis, we should be able to devise informed strategies to turn them off.”

Dentistry researchers are particularly equipped to study fibrosis via gum disease. “The nice thing about periodontal disease is it doesn’t kill people, but it’s linked,” says McCulloch. “And it’s much easier to study than these other systems. You can sample tissue easily.”

“The goal of this research is to understand the fundamental mechanism of action of fibrosis, but also identifying drug targets,” says McCulloch. That could include identifying existing drugs that could halt or control fibrosis, or pathways to create new medications, all of which could impact the health of millions.