Finding the biomarkers of pain

By Diane Peters

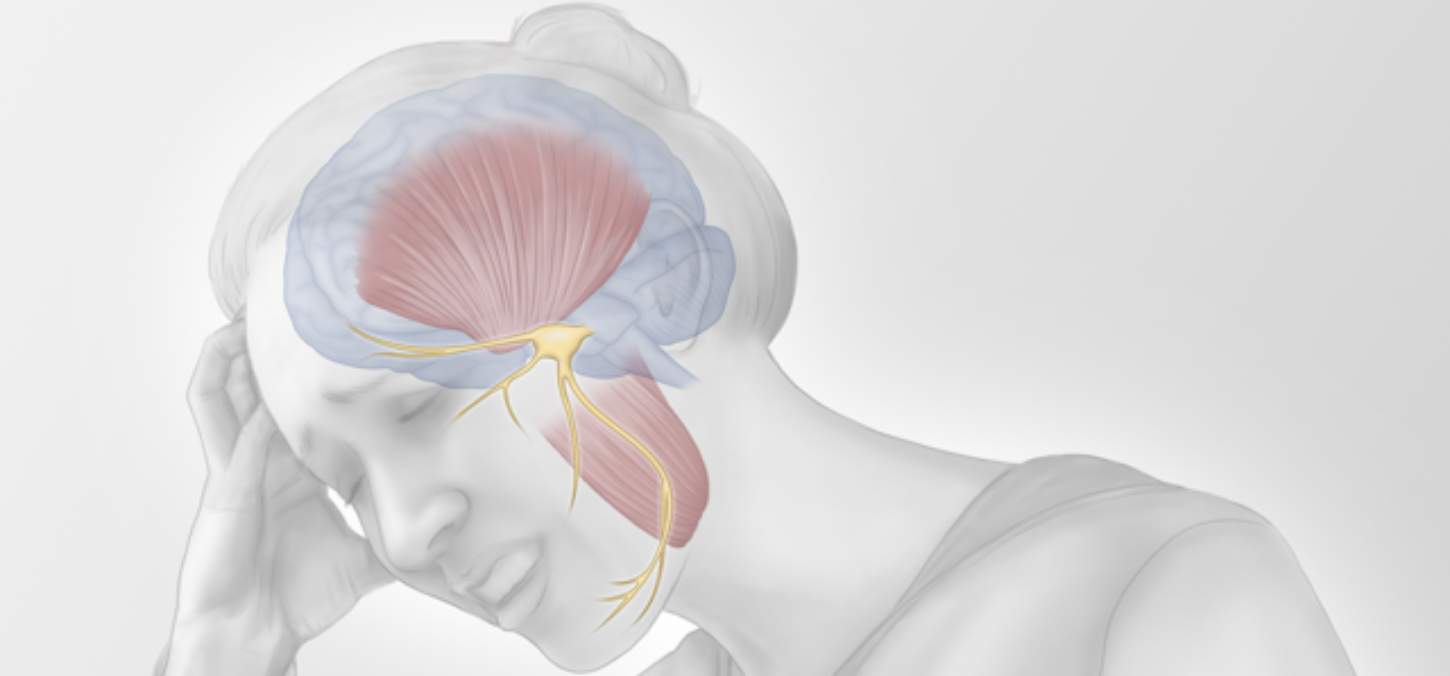

A new Faculty study seeks to discover more about debilitating TMD

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is the most common cause of orofacial pain, affecting 8-12 per cent of Canadians, and yet we know far too little about it. A new study from the Faculty of Dentistry seeks to fully assess the biological underpinnings of this disorder.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research have awarded a research team $830,000 over five years — in addition to an initial $100,000 a year ago for the same project — to identify a biological signature of TMD. Researchers will be looking at muscles and nerves related to the condition in a multi-centre trial of about 300 people.

“TMD is a huge cause of orofacial pain, but it’s understudied,” says Massieh Moayedi, assistant professor at the Faculty and co-principal investigator of the study. “Problems such as back pain are much more common. But we believe that orofacial pain is very different from other pain in the body.”

Indeed, more 30 per cent of people with TMD are still in pain five years after their diagnosis, which means current treatment approaches are not effective.

As well, there is the need to know more about trigeminal neuropathic pain (TNP), a related facial pain condition.

The issue may begin with diagnosis. Currently, dentists and physicians diagnose facial pain disorders by palpating facial muscles and asking for verbal reports of pain and its impact on function. “At the end of the day, it’s very subjective,” says Iacopo Cioffi, assistant professor at the Faculty and co-principal investigator of the study. “We don’t know what’s going on in their mouths and with their nerves.”

He says understanding the mechanisms behind TMD and TNP could help doctors make a more objective, less binary diagnosis, allowing them to categorize these conditions from mild to severe.

With more information, doctors could match treatment to biological causes. Currently, most people with facial pain get a treatment approach that starts conservatively, ramping up patient education, jaw exercises, behavioural therapy, night guards and centrally acting medications to see what works. Meanwhile, the approach can vary widely between individual doctors.

For his role in the trial, which will includes TMD and TNP patients and controls in Canada and Australia, Cioffi will use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess the structure of chewing muscles, near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) to measure muscle oxygenation, and electomyography (EMG) to measure muscle function.

Meanwhile, Moayedi will be using functional MRI to track brain activity to understand the role nerves play in these diseases. “We’re going to look at brain network activity and what systems are affected,” he says. Ultimately, they plan to integrate these lines of research to find a biomarker.

After itemizing biological characteristics of TMD and TNP, the researchers hope to go further. “Finding biomarkers is just a first step,” says Moayedi.

He says the research team expect to follow up this research with an assessment of which treatments most effectively impact specific biomarkers. From there, as well, researchers could look to develop targeted medications or therapies.

Understanding this surprisingly complex and debilitating pain condition could also discover more about its origins, says Moayedi. “It opens the door to how we can prevent it.”

Photo: Illustration showing temporomandibular disorder pain (Created by Ann Sanderson)